The struggle for sleep: let’s not doze off on teen sleep epidemic

December 24, 2018

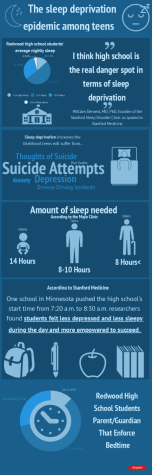

Adequate sleep is uncommon for most high school students. Only 31 percent of Redwood students receive the recommended amount of sleep of eight to nine hours, according to a recent self-reported Bark survey. Lack of sleep can be detrimental to teens’ health, according to the UCLA Disorder Center. Especially at such a pivotal age in students’ life where there is significant brain development, lack of sleep can result in suicidal thoughts or actions, depression, poor grades or a poor social life.

As students progress through their education, pressures mount and inhibit completion of a full night’s sleep, put off for the sake of an essay or after-school activity. On top of those commitments, some students push themselves academically with Advanced Placement (AP) and honors classes, studying for ACT or SAT tests and college applications. A study from the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) reported that an insufficient amount of sleep negatively affects learning and development in students, and can alter judgment.

Across America there are teens suffering from a detrimental lack of sleep and according to the Bark survey, only four percent of Redwood High School students receive 10 or more hours of sleep nightly, 52 percent of students receive six to seven hours of sleep nightly and 13 percent receive five or less hours of sleep per night. Before puberty, children will typically feel sleepy at around eight or nine p.m., but as they enter adolescence, they do not begin to feel sleepy until 10 or 11 p.m. Because of the shift in teen’s circadian rhythm, an internal clock that controls humans need to sleep, according to UCLA Health. It is particularly difficult for teens who regularly fall asleep past midnight to get the necessary amount and quality of sleep.

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is the type of sleep that occurs during intervals in the night, and scientists have found that non-REM sleep, the type people experience between 10 p.m. and three a.m., is deeper and more restorative than lighter REM sleep, which occurs between three and seven a.m. Teens who regularly go to bed at three a.m., for example, will get fewer hours of restorative non-REM sleep, even if they sleep until noon, according to U.S. News.

Principal David Sondheim acknowledged how difficult it is for students to receive a healthy amount of sleep, given all the commitments students have, along with the academic pressure students are under.

“It is a challenge [for students to get enough sleep] here because we have students, parents and staff who all want to be high-achieving. Everybody wants to do well and people are more willing than they should be to give up on sleep to make that happen,” Sondheim said.

JAMA reported that over 70 percent of high school students receive less than eight hours of sleep per night. In October, JAMA conducted an experiment where they evaluated teens’ amounts of sleep and “risky” behavior. They reported that teens were three times more likely to consider suicide, plan a suicide attempt or attempt suicide if they slept for less than six hours per night. Those students who slept six hours or less were also four times more likely to have a reported suicide attempt that resulted in treatment.

Redwood seniors Lizzie Roper and Jack Suchodolski became interested in sleep patterns and habits among teens at the beginning of this school year, and chose it as the topic for their Independent Science Research project because they felt that this issue affects them as students. Roper and Suchodolski wanted to know more about the quality of sleep students receive, so they conducted a study observing the amount of sleep and the quality of sleep that students are getting. They considered factors such as class schedule, extracurricular activities and course rigor.

Roper and Suchodolski are having participants use nightly sleep logs as well as an app, Sleepzy, that tracks the quality of each students’ sleep.

“There is almost a split between students who are dedicated to getting the same amount of sleep every night, where there are kids who go to bed and 10:30 p.m. and stop their homework no matter what and they have had pretty consistent sleep, and there are people who continue homework until they’re done with it and then go to sleep,” Suchodolski said.

Junior Nathan Ross gets as little as five hours of sleep per night, and reports feeling drowsy in class.

“I feel kind of heavy; nothing seems really that interesting, and a lot of the times I can’t focus. I feel kind of fidgety because I need something to do to keep me awake. If I’m not doing something I will just fall asleep in the middle of class or homework,” Ross said.

Not only can sleep deprivation affect students’ overall health, but it also affects their quality of learning, according to Ross.

“I think part of the reason a lot of the times I’m behind in my classes is because I’m always tired and distracted, which makes it harder to do work,” Ross said.

Experts in sleep and teen health have found that changing school start times is part of a larger solution to the lack of sleep students receive, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“It’s different for us biologically, so to have things like school start at the same time from when we were young to now; it’s interesting to see that there aren’t accommodations for biological changes that are going through our bodies,” Suchodolski said.

Addressing this issue was a recent government legislation in California. On Aug. 31, 2018, the California State Assembly passed the School Start Time Bill, or SB 329, which requires middle, high and charter schools to start no earlier than 8:30 a.m.

The stress that leads to a detrimental lack of sleep comes from many places. There is pressure from parents to succeed, from teachers to do well and from peers to get good grades, as well as the daunting college process, according to Sondheim.

“I think it comes from the media and the news that paint the picture that it’s difficult-to -impossible to get into college, when the reality is there are lots and lots of colleges and lots and lots of opportunities for students who have achieved [at] a variety of different levels,” Sondheim said.

The extreme effects on health and education make teens’ lack of sleep a pressing issue, according to Suchodolski.

“It’s more essential that we focus on sleep now than later on when it doesn’t matter as much, because what we do now sets the tone for what our lives are going to look like later. So, if people don’t take that into account and do ‘all-nighters’ all the time, it’s not the healthiest decision,” Suchodolski said.

There are so many factors that contribute to teen’s sleep deprivation and there is not just one solution. According to Stanford Medicine, to address the sleep deprivation epidemic among teens, schools need to reconsider start times not just in California and adjust expectations and pressures that affect students sleep. A few things teens can do to is try to stay off electronics before bed, maintain a regular bedtime and prioritize getting to sleep over school work. The perception that teenagers need to overextend themselves in high school in order succeed later is harmful, according to Suchodolski, and must be corrected.

“[The] idea that we have to do everything [now] to set us up for a better future is a stigma that we have to break,” Suchodolski said.