Whether by heart attack or Huntington’s disease, death is an inevitability humans must confront. As devastating diseases continue to claim lives, scientists are left with the ultimate task: finding cures. Combating and eventually eradicating conditions is the goal of aging researchers.

Longevity:

Longevity, a long, fruitful life filled with youth and splendor, is the dream of many. With improvements in preventative medicines and life-extending technologies, our generation may well be the one that averages 100 plus years of life, aging researchers believe.

In the book, The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, author Raymond Kurzweil describes a “technological singularity” in the year 2045, a point where he believes progress will be so rapid that artificial intelligence will trump human intelligence. People will augment their minds and bodies with genetic alterations, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence, living indefinitely, Kurzweil claims.

Dr. Aubrey de Grey, Chief Science Officer at Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence Foundation (SENS), an aging research center, believes the allure of life-extension is obvious.

“People tend to fixate a lot on the longevity consequences of medicine, and it is not surprising that people do, because various medical technologies may lead to longer lifespans,” de Grey said.

The average American today lives 78.8 years, according to the Center for Disease Control.

Grounded in science, the first step toward increased longevity begins with the improvement of preventative medicine, according to de Grey.

“Two things that will be drastically different in healthcare will be the way in which we choose who we give medicine to and also the number of medicines we give them,” de Grey said. “Today, by and large, people don’t get medical treatment until they are sick, which is a problem. We need more preventative medicines that one takes before getting sick.”

Longer lifespans may also be achieved by finding the best ways to combine medicines, de Grey said.

“We are going to be giving people combinations of various medicines all at the same time,” de Grey said, adding that medical professionals are rightly hesitant of doing so today. “But we are going to challenge those boundaries because some medicines may work better when taken in conjunction with another pill.”

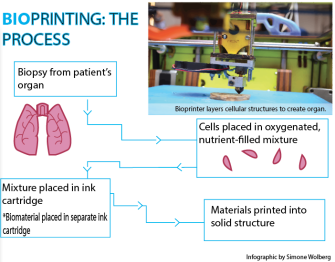

Bioprinting, or the printing of human organs, is another technology that may increase longevity.

Researchers at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine have made key advancements in the bioprinting industry.

“Our team has already successfully engineered bladders, cartilage, skin, and urine tubes that have been implanted in patients,” wrote Dr. Anthony Atala, the director of the institute, in an email interview. “Our goal is to produce organ structures with 3D printing to make the engineering process more precise and reproducible.”

Bioprinting uses the patient’s own cells so that the organ is not “rejected” by the patient’s body, Atala wrote.

Once the bioprinted organ is placed in the body, it functions as a normal organ without additional mechanical assistance, according to Atala.

Ensuring that the bioprinted organs will have enough oxygen to stay alive during surgery is a serious challenge, according to Atala. Options to combat this include bioprinting oxygen-generating materials like blood vessels or micro-channels.

On average, 21 people die each day in the United States waiting for organ transplants due to organ shortages, according to studies from the U.S. Department of Health. Bioprinted organs could eliminate this problem. A doctor in the near future could potentially be able to “print” and surgically implant the organ his patient needs in a matter of hours, according to Atala.

“The ultimate goal of regenerative medicine—regardless of the way the organs are engineered—is to help solve the shortage of donor organs,” Atala wrote.

The quest for cures:

Lethal medical conditions such as Alzheimer’s and cancer have stood the test of time, evading 100 percent effective treatment.

Scientists from SENS are hoping to change that. The foundation tests whether regenerative medicine, the study of regeneration of human parts, can slow the aging process and eradicate disease.

“When I talk about our work, I often call it the sweet spot between prevention and treatment,” de Grey said. “At SENS, we try and balance our research between repairing damage already caused with stopping damage from being created in the first place.”

Heart disease and stroke are the top two killers of Americans today, according to the American Heart Association. Atherosclerosis, a common cardiovascular disease that can lead to stroke, is one of many conditions studied at SENS.

“About 15 years ago, I proposed an approach that was completely new for combating atherosclerosis,” de Grey said. “The approach was taking bacteria that could break down 7-ketocholesterol, a toxic cholesterol molecule, and inserting it into a modified human cell.”

7-ketocholesterol is harmful cholesterol that, in excess amounts, can clog one’s arteries and increase blood pressure.

Once these modified cells were functioning in the body, the 7-ketocholesterol could be broken down into something that wasn’t toxic anymore, according to de Grey.

In the last two years, one of de Grey’s teams at Rice University made a large breakthrough in this research.

“It didn’t take us very long to find the bacteria and then the genes it uses to target toxic cholesterol molecules. The hardest part, however, was making those genes work in the human cell, and we just made that breakthrough about a year or two ago,” de Grey said.

SENS is furthering work towards heart disease prevention by improving its medicines.

De Grey’s team hopes to modify a group of preventative drugs that lower cholesterol, known as Statin drugs.

“Statins are not ideal because they stop production of good cholesterol as well as bad 7-ketocholesterol. That is a problem because the good cholesterol is an essential molecule,” he said.

Another, more complex set of diseases is on de Grey’s agenda: cancer. Cancers are diseases characterized by the uncontrolled growth of mutated cells known as tumor cells, and it can occur almost anywhere in the body.

There will be an estimated 1,658,370 new cancer cases diagnosed and 589,430 cancer deaths in the United States this year, according to the American Cancer Society.

“Cancer is the hardest concept of aging to combat because it has its own evolution going on. Each cell is trying to adapt to whatever we do to it,” de Grey said.

In order to combat cancer, new treatments have to be explored, de Grey believes.

“Chemotherapy and radiotherapy don’t work very well. SENS, along with Geron and other institutes, is exploring using the immune system to combat [cancer],” de Grey said.

Currently, biotechnology researchers at Geron Corporation have two anti-cancer products in human clinical trials.

Telomerase is a component of Geron’s anti-cancer products. It works to kill cancer because it attacks the DNA of cancer cells, specifically the ends of the chromosomes, called telomeres. Without the telomere, the cell will die quickly, according to de Grey.

Ethical complications:

Though the Fountain of Youth is often thought of idealistically, the majority of Americans report that they personally do not want medical treatments that would allow them to live decades longer.

According to a 2013 PEW Research survey, 56 percent of Americans would not personally want to receive treatments that would allow them to live at least until the age of 120. Sixty-nine percent of those surveyed said that their ideal life span is between 79 and 100 years old.

“Just like how some people opt out of life support, others will certainly have reservations towards new biotechnologies,” said Dr. Moira Gunn, USF assistant professor and host of National Public Radio’s BioTech Nation.

De Grey believes there isn’t a dichotomy between quality and quantity of life.

“I am very much in favor of longevity, but it is a side effect of health,” de Grey said. “People think there is a difference between the quality of life and the quantity of life. But the whole point of this medicine is to stop that from being true to make it so that quality of life actually delivers quantity of life.”

Though 79 percent of Americans think that everyone should have access to longevity treatments such as bioprinting, 66 percent believe that only the wealthy would actually have access to such treatments, according to Pew Research.

Whether this perception could be reality is currently unknown for pioneering treatments like bioprinting, according to Atala. This is because bioprinted organs are only available through research studies and no prices are set yet.

Another major ethical consideration in the advancement of bioprinting, aside from financial availability, is how to decide who will receive organs for transplantation.

Due to the current shortage of organs for transplantation, doctors and surgeons often must make tough decisions about who will receive an organ and who will not. Though bioprinting can begin to minimize the shortage of organs, it would take many years for the gap to be closed completely, if at all.