It’s a typical cross country practice for junior Mary Monda Oewel. Besides the familiar sounds of her feet pounding on a trail and steady, even breathing, she and her teammates are distracted from their run by a shrill whistling noise coming from someone in a car riding down the street on their left.

They’re being catcalled.

“I haven’t told anyone because I don’t think there is anything that I can do about it. It’s just a fact that I may have to run with disturbances,” she said.

Oewel is a victim of street harassment, a form of sexual harassment defined by anti-street harassment organization Stop Street Harassment as “unwelcome words and actions by unknown persons in public places which are motivated by gender and invade a person’s physical and emotional space in a disrespectful, creepy, startling, scary, or insulting way.”

Examples of street harassment include leering, catcalls, sexually charged comments, vulgar gestures, flashing sexualized body parts, and even sexual assault and rape.

One in four girls will experience street harassment by the age of 12, and nearly 90 percent of women will experience it by the time they are 19, a 2008 survey of 811 women conducted by Stop Street Harassment claimed.

Junior Daphne Nhuch first experienced street harassment in April, when she was verbally harassed while shopping in the Haight with a group of friends.

“We all felt fairly uncomfortable,” she said, adding, “No one [around us] really reacted. It just seemed like a normal event.”

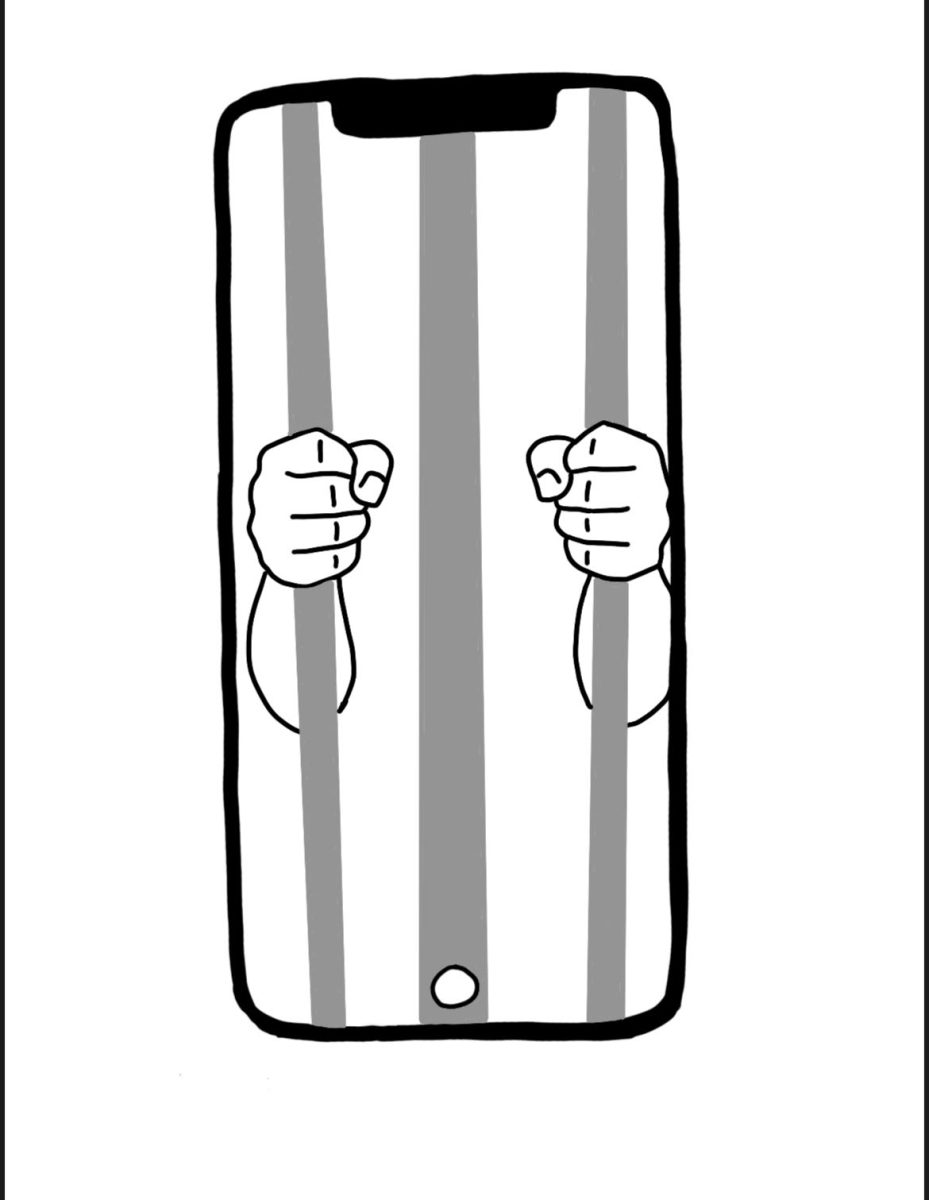

Emily May, co-founder and executive director of an international organization known as Hollaback!, is working to make street harassment seem less normal and inevitable. She encourages victims of sexual harassment to speak out against their harassers, often via social media or other creative formats.

“I encourage everyone to share their story,” May said. “It is key to establishing empathy among people who don’t get harassed.”

Hollaback! uses social media to raise awareness, particularly with a new app that allows victims of street harassment to map where their experiences have occurred. May said that by using tools like this to share stories of harassment, other victims will no longer feel alone in their struggle.

“When we understand it isn’t our fault, we get a lot more motivated to take action,” May said.

Jennifer Scott, a board member of Stop Street Harassment, said that though there is a common belief that street harassment should be taken as a compliment or that it should be treated as a joke, street harassment is a serious issue that affects many victims’ lives.

“If you ask women how many of them are uncomfortable walking on the street by themselves, particularly at night, the vast majority are going to tell you that they are,” she said. “And that’s an impact of…knowing what can potentially happen to them. Or the number of women who tell you, ‘I have adopted a different route to work,’ or ‘I have made conscious decisions to change the clothing that I wear, to try to avoid being street harassed.’ Those are other impacts too, in addition to how it might affect someone socially or emotionally.”

A Stop Street Harassment study claimed that 37 percent of those interviewed said that they wore certain clothes purposely at least once a month to attract less attention, and 10 percent said they always did. Fifty percent said they crossed streets or took other routes at least once a month to avoid street harassment, and 16 percent said they always did this.

Additionally, 45 percent of women in the survey said they felt uncomfortable being out at night or after dark at least monthly, with 11 percent always feeling that way, and 40 percent said they avoided being out alone, with 8 percent saying they always felt that way.

Though directly confronting a harasser is sometimes an effective way of handling street harassment, sometimes when women directly confront their harassers, they are further harassed, Scott stated.

“[Street harassment is] about power and control,” Scott said. “If it were about giving someone a compliment, and you realized that something you said made that person really uncomfortable, you’d apologize. You’d quit doing it.”

“But sometimes when women respond to their harassers, or not just women, anyone who’s street harassed, it makes the situation escalate. Then he calls her a ‘bitch,’ for not understanding his compliment, et cetera,” she said.

Harassers sometimes respond in that way as a way of retaining dominance, according to Scott.

“It’s about the harasser’s ability to have some control over the situation, to use their power and privilege to say, ‘I can speak to you in this way, and then I can dictate how you’re obligated to respond to it.’”

Scott said that one reason street harassment is ignored is that there is a misconception that words cannot be damaging.

“The fact that street harassment doesn’t always involve a sexual assault doesn’t mean it’s not serious,” she said. “We live in a society where we teach our children ‘sticks and stones,’ the rhyme about ‘words can’t hurt me.’ That does two things. One, it silences people, because it says, ‘Oh, I’m supposed to not be impacted by this, I’m supposed to not be affected, this isn’t supposed to be a big deal, what’s wrong with me that I’m upset about it?’ And it also means, ‘Because I can’t talk about it, I can’t do anything about it.’”

Because of this mentality, street harassment is not discussed as much as it should be, according to Scott.

“[Talking about street harassment] isn’t really common anywhere, really, other than with those who do anti-harassment work,” she said. “We’re trying to make it a common conversation, make it comfortable for people to be able to talk about it.”

Both May and Scott emphasized the importance of sharing stories and reporting instances of street harassment.

“The more people who decide that they want to make reports, the more awareness the folks who are being reported to will have of the seriousness of the issue, and that can only help things,” Scott said.

For more resources regarding street harassment:

Stop Street Harassment’s list of California laws related to street harassment, as well as procedures for reporting instances of street harassment: http://www.

Additionally, May said that Hollaback! will be releasing a guide for teachers and administrators regarding students’ street harassment.